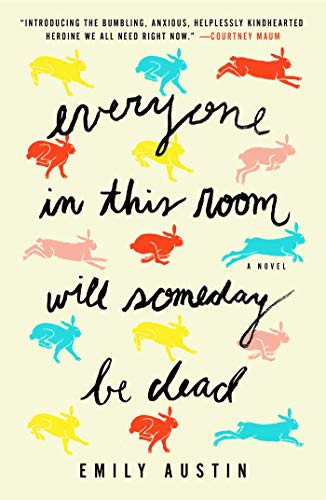

Everyone in This Room Will Someday Be Dead

Gilda, the main character in this story of debilitating obsessions, is a woman in her late 20s unable to get it together enough to establish a reasonable life. She checks out a therapy group at a Catholic church, is mistaken for a job applicant and is offered an administrative assistant position recently opened by the previous assistant’s death. Despite being lesbian and an atheist, she accepts. Apart from having a job, this seems like a disastrous decision, but it becomes clear further into the book, if it wasn’t already, that there’s not much that can slow her descent into despair and dissolution.

Putting someone like Gilda at the heart of a story is tricky because she’s incapable of generating plot. The plot shreds that exist are the result of other people or things bumping against her, and watching what happens: she searches for a missing cat, she’s fixed up …

Gilda, the main character in this story of debilitating obsessions, is a woman in her late 20s unable to get it together enough to establish a reasonable life. She checks out a therapy group at a Catholic church, is mistaken for a job applicant and is offered an administrative assistant position recently opened by the previous assistant’s death. Despite being lesbian and an atheist, she accepts. Apart from having a job, this seems like a disastrous decision, but it becomes clear further into the book, if it wasn’t already, that there’s not much that can slow her descent into despair and dissolution.

Putting someone like Gilda at the heart of a story is tricky because she’s incapable of generating plot. The plot shreds that exist are the result of other people or things bumping against her, and watching what happens: she searches for a missing cat, she’s fixed up with an obnoxious male life coach, and, in the most serious shred, questions come up about the previous assistant’s death. Left by herself, she obsesses about death — hers and particularly her pet rabbit’s when she was ten — about her having a skeleton under her skin and about being an infinitely small object in an infinitely large universe. Other people paralyze her with the fear of causing sadness or disappointment. She got an inappropriate job because she didn’t want to embarrass a priest, it’s why she goes out with an obnoxious male life coach and why she continues an e-mail correspondence with a friend of the former assistant who doesn’t know she’s dead.

This sounds grim, and from one point of view it probably is, but Austin’s straightforward, sharp writing uses basic shapes and primary colors to present delicate matters. The story is schematic — How tall is Gilda? What color is her hair? — which moves it along at a good clip, unobstructed by sentimentality or pathos. It isn’t black comedy, but it has its moments. Like a good prole, Gilda steals stuff from work, but in her case it’s the blood and body of Christ, which she discovers when she goes on-line to leave a negative review at the web site of the manufacturer of the bland and insubstantial crackers she’s been eating. And, of course, the ol’ favorite: at confession she admits to eating pork. In the other direction, there’s her horrible family, the shameful way she treats her girlfriend, and her habitual lying. And her mental health. Austin’s firm, sure grip turns all of this into a good, if not necessarily edifying, ride.